Have you ever found yourself in the following situation?

You’re progressing well with your Hebrew vocabulary and have just picked up a shiny new Hebrew word or two, but you don’t know how to use them correctly in a sentence.

If you’re still left scratching your head about the proper order of words in Hebrew sentences and questions, HebrewPod101 is here to help you make sense of it all and put your thoughts and words in order with our guide on Hebrew sentence structure and word order.

Did you know that the most commonly heard word in Hebrew is בסדר (beseder)? Though it’s usually the equivalent of “OK” in English, it literally means “in order.” This hints at the great importance that Hebrew and Jewish culture in general place on ordering things. And words are no exception. Syntax—the correct order and position of words in sentences and questions—is as important in Hebrew as it is in English (and most other languages) for effective communication.

While Hebrew sentence structure isn’t terribly different from that in English, there are definitely some distinctions we want to be aware of. Luckily, this topic isn’t too complex, so just sit back, relax, and enjoy organizing those words you’ve been studying into structures. Because there’s nothing quite as satisfying in language-learning as being able to piece it all together and start speaking full sentences. Here we go!

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

- Overview of Word Order in Hebrew

- Basic Word Order with Subject, Verb & Object

- Word Order with Prepositional Phrases

- Word Order with Modifiers

- Word Order in Questions

- Translation Exercises

- HebrewPod101 is Here to Help You Put Your Hebrew in Order!

1. Overview of Word Order in Hebrew

The truth is that modern Hebrew word order has changed significantly since Biblical times, which is good news for you. Whereas the word order in Biblical Hebrew has verbs coming before both the subject and predicate, modern Hebrew usually follows the same basic sentence structure as English, where the predicate is a verb: Subject-Predicate. Note that this order can be modified in some cases, such as for emphasis, so it’s still possible to have the verb come before the subject. However, as noted, the norm is the same as in English, i.e. the subject will come before the verb.

To be considered complete, a Hebrew sentence will always contain a subject and at least one predicate. However, as hinted above, the predicate is not necessarily always a verb in Hebrew. (We’ll get into specifics a bit later on.) Obviously, Hebrew sentences can, and often do, contain other elements, such as adverbs, conjunctions, and so on. However, the basic minimum structure, as in English, is Subject-Predicate.

2. Basic Word Order with Subject, Verb & Object

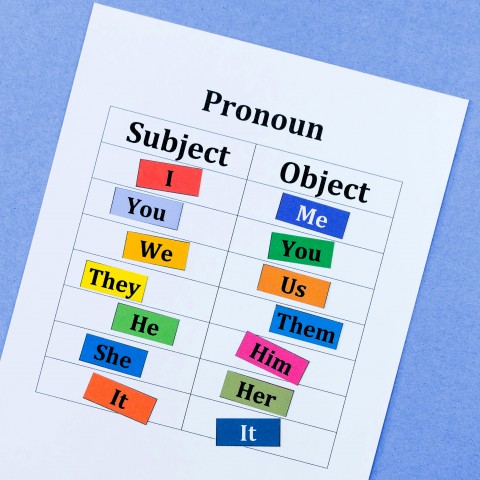

Just so we’re clear, let’s define the words “subject,” “verb,” and “object” before we go any further. In the context of grammar, the subject is the agent or the noun that is behind the verb. The verb is the action or condition word. The object is the noun that the subject is acting upon or affecting through the verb. With that in mind, let’s take a look at a simple example of how this plays out:

אני לומד עברית.

Ani lomed Ivrit.

“I study Hebrew.”

Here, you can see the same syntax as in English, and, as mentioned, most sentences will indeed follow this structure.

That being said, because the grammar of Hebrew is different from that of English, let’s have a look at a couple of basic rules and principles to help you understand the correct word order to use in Hebrew.

1. In cases where the conjugated form of a verb clearly indicates who the subject is in terms of gender, number, and person, it’s common to drop the pronoun. Compare these two sentences:

- אני לומד עברית כל יום.

Ani lomed Ivrit kol yom.

“I study Hebrew every day.”

- למדתי עברית אתמול.

Lamadeti Ivrit etmol.

“I studied Hebrew yesterday.”

In the first sentence, the conjugated form לומד (lomed), meaning “study,” can be used for different singular masculine persons (first, second, or third), so we must use the correct pronoun to indicate which person is being used. However, in the second sentence, the conjugated form למדתי (lamad’ti), meaning “studied,” indicates the first person singular, so we don’t need to use the pronoun אני (Ani), meaning “I.”

2. When the subject is indefinite, i.e. someone or something unknown or nonspecific, we’ll often see the order Verb-Object-Subject. For example:

- סיפרו לי שאתה לומד עברית.

Sipru li she-atah lomed Ivrit.

“Someone told me that you are learning Hebrew.”

[Literally: “(They) told me that you are learning Hebrew.”]

- הגיע בשבילך משהו בדואר.

Higi’a bishvil’kha mashehu ba-do’ar.

“Something came for you in the mail.”

[Literally: “Came for you something in the mail.”]

3. Another unique feature of Hebrew is that, in the present tense, the verb להיות (lehiyot), meaning “to be,” is omitted. We still have a predicate, but no verb (unless there are additional verbs in the sentence). Compare the following examples:

- דניאל היה תלמיד טוב.

Daniel hayah talmid tov.

“Daniel was a good student.”

- דניאל תלמיד טוב.

Daniel talmid tov.

“Daniel is a good student.” [Note there is no verb here!]

4. The verb להיות (lehiyot), meaning “to be,” appears in the past and future tenses without a subject to denote existence, or with an adjective used as a predicate, such as in the following examples:

- היה לי חבר אמריקאי שלמד עברית בירושלים.

Hayah li khaver Amerika’i she-lamad Ivrit be-Yerushalayim.

“I had an American friend who studied Hebrew in Jerusalem.”

- יהיה כיף ללמוד עברית בירושלים.

Yihiyeh keyf lilmod Ivrit be-Yerushalayim.

“It will be fun to study Hebrew in Jerusalem.”

5. Hebrew has no verb for “to have.” In the past and future tenses, we use the verb להיות (lehiyot), meaning “to be,” followed by a possessive pronoun. In the present tense, we use the word יש (yesh), which means “there is/are,” followed by a possessive pronoun. Following are some examples in all three tenses:

- היה לי חבר שלמד עברית בירושלים.

Hayah li khaver Amerika’i she-lamad Ivrit be-Yerushalayim.

“I had an American friend who studied Hebrew in Jerusalem.”

- יש לי חבר אמריקאי שלומד עברית בירושלים.

Yesh li khaver Amerika’i she-lomed Ivrit be-Yerushalayim.

“I have an American friend who is studying Hebrew in Jerusalem.”

- יהיה לי זמן לפגוש חברים בירושלים.

Yehiyeh li zman lifgosh khaverim be-Yerushalayim.

“I will have time to meet friends in Jerusalem.”

6. The opposite of יש (yesh), meaning “there is/are,” is אין (eyn), meaning “there is/are not,” followed by a possessive pronoun. For past and future tenses, we again use לא (lo) to create the negative form of the verb להיות (lehiyot), or “to be,” followed by a possessive:

- לא היה לי זמן לבשל משהו טעים.

Lo hayah li zman levashel mashehu ta’im.

“I had no time to cook something tasty.”

- אין לי זמן לבשל משהו טעים.

Eyn li zman levashel mashehu ta’im.

“I have no time to cook something tasty.”

- לא יהיה לי זמן לבשל משהו טעים.

Lo yehiyeh li zman levashel mashehu ta’im.

“I will not have time to cook something tasty.”

7. Another unique feature of Hebrew is that the particle את (et) must be used prior to all definite direct objects as an accusative marker. Note how this looks in terms of sentence structure:

- הוא אכל את הפלאפל.

Hu akhal et ha-falafel.

“He ate the falafel.”

- היא מוכרת את האוטו שלה.

Hi mokheret et ha-oto shelah.

“She is selling her car.”

- אנחנו נסדר את הספרים.

Anakhnu nesader et ha-s’farim.

“We’ll organize the books.”

3. Word Order with Prepositional Phrases

Now that we’ve looked at basic sentence structures, let’s see how Hebrew word order changes when we add prepositional phrases to our sentences. Prepositions are words that establish a relationship between two other words (an object and an antecedent). But don’t worry if this all sounds too technical, because when you see some examples, you’ll surely recognize just what we’re talking about.

A prepositional phrase is a phrase that employs such a prepositional relationship, and it’s used like an adjective in order to describe a noun or pronoun. As in English, these can come before or after the noun or pronoun they describe. Let’s see some examples to make more sense of it all.

One way to think about prepositions is that they answer information questions, such as “When?” “Where?” and “Why?” Hebrew has eleven types of prepositions, but to simplify matters—and because our focus is on word order—we’ll look at the more common types and see the usual position of the prepositional phrase within the sentence. The prepositional phrases have been bolded to help show their location within the sentence, which is either directly after the noun or pronoun they describe, or either before or after the verb that goes with that noun or pronoun. Most of the time, the logic is the same as in English.

1. Position (answer questions like on what, next to what, under what, etc.)

- הספר על השולחן הוא שלי.

Ha-sefer al ha-shulkhan hu sheli.

“The book on the table is mine.”

- אכלתי את הפיצה שהייתה על המדף העליון במקרר.

Akhalti et ha-pitzah she-hayitah al ha-madaf ha-elyon bamekarer.

“I ate the pizza that was on the top shelf in the refrigerator.”

2. Direction (answer questions like where [to], from where, toward what, etc.)

- רונית רצה לכיוון בית הספר.

Ronit ratzah le-kivun beyt ha-sefer.

“Ronit ran toward the school.”

- נסענו באוטו לתוך הלילה.

Nasa’nu ba-oto letokh ha-laylah.

“We drove into the night.”

3. Time (answer questions like before what, after what, during what, etc.)

- נאכל אחרי טקס הסיום.

Nokhal akharey tekes ha-siyum.

“We’ll eat after the graduation ceremony.”

- בזמן שישנת הכנתי ארוחת בוקר.

Be-zman she-yashanta, hekhanti arukhat boker.

“While you slept, I made breakfast.”

4. Cause, Agency, or Source (answer questions like of what, for what, about what, etc.)

- שתינו שתי כוסות יין.

Shatinu shtey cosot yayin.

“We drank two glasses of wine.”

- יפעת קוראת ספר על מלחמת העולם השנייה.

Yif’at koret sefer al Milkhemet ha-Olam ha-Shniyah.

“Yifat is reading a book about the Second World War.”

4. Word Order with Modifiers

Now, let’s take a look at modifiers, which are just what they sound like: words that modify nouns. These include adjectives, determiners, numbers, possessive pronouns, and relative clauses. We’ll look at each category separately to see where they go in terms of Hebrew word order.

1. Adjectives

Contrary to the rules of English syntax, adjectives in Hebrew will always appear after the noun they describe. Notice that in the case of definite nouns, the article before the adjective (and the one before the noun) describes the noun.

- רמון המקסיקני לומד עברית.

Ramon ha-Meksikani lomed Ivrit.

“Mexican Ramón studies Hebrew.”

- התלמיד המקסיקני לומד עברית.

Ha-Talmid ha-Meksikani lomed Ivrit.

“The Mexican student studies Hebrew.”

2. Determiners

Determiners, such as “this” or “that,” will likewise always come after the noun they describe.

- התלמיד הזה לומד עברית.

Ha-Talmid ha-zeh lomed Ivrit.

“This student studies Hebrew.”

- התלמידה ההיא לומדת עברית.

Ha-talmidah ha-hi lomed Ivrit.

“That student studies Hebrew.”

- התלמידים האלה לומדים עברית מהספר הזה.

Ha-Talmidim ha-eleh lomdim Ivrit me-ha-sefer ha-zeh.

“These students study Hebrew from this book.”

3. Numbers

As in English, numbers will always precede the noun when indicating the quantity of that noun.

- שלושה תלמידים לומדים עברית.

Shloshah talmidim lomdim Ivrit.

“Three students study Hebrew.”

- מריה לומדת עברית אצל שני מורים פרטיים.

Mari’a lomedet Ivrit etzel shney morim prati’im.

“Maria studies Hebrew with two private tutors.”

4. Possessive pronouns

Unlike in English, possessive pronouns appear after the noun they’re attached to.

- אמא שלי לומדת עברית.

Ima sheli lomedet Ivrit.

“My mother studies Hebrew.”

- העברית שלך טובה מאוד.

Ha-Ivrit shelakh tovah me’od.

“Your Hebrew is very good.”

5. Relative clauses

Relative clauses in Hebrew, as in English, follow the noun they describe.

- שכן שלי שנסע לירושלים למד עברית באוניברסיטה.

Shakhen sheli she-nasa le-Yerushalayim lamad Ivrit ba-universitah.

“A neighbor of mine who went to Jerusalem studied Hebrew at the university.”

- הוא למד בקמפוס שנמצא בהר הצופים.

Hu lamad ba-kampus she-nimtsa be-Har Ha-Tzofim.

“He studies at the campus that is on Mt. Scopus.”

5. Word Order in Questions

Yet another difference (and a welcome one this time) between Hebrew and English is that in Hebrew, questions share the same word order as other sentences. This means you don’t need to worry about changing word order when asking questions. It’s simply a matter of adding the relevant question word to precede the rest of your words. Here are some examples of questions and answers to illustrate:

- –מתי אתה נוסע לחו”ל?

Matay atah nose’a le-khul?

“When are you traveling abroad?”

-אני נוסע לחו”ל בעוד חודש.

Ani nose’a le-khul be-od khodesh.

“I’m traveling abroad in a month.”

- –מי רוצה גלידה?

Mi rotzeh glidah?

“Who wants ice cream?”

-כולנו רוצים גלידה!

Kulanu rotzim glidah!

“We all want ice cream!”

- –איפה שמת את הארנק שלי?

Eyfoh samt et ha-arnak sheli?

“Where did you put my wallet?”

-שמתי את הארנק שלך מעל המקרר.

Samti et ha-arnak shelkha me’al ha-mekarer.

“I put your wallet on top of the refrigerator.”

6. Translation Exercises

Now let’s test your knowledge on what we’ve covered here with some translation exercises. We’ll start with simple sentences and work up toward more complex ones. See if you can translate these without looking back to the lesson. The answers are provided below.

1. Ben and Julie study Hebrew.

2. Ben and Julie study Hebrew in Jerusalem.

3. Ben and Julie study Hebrew with two private tutors in Jerusalem.

4. Where do Ben and Julie study Hebrew?

5. With whom do Ben and Julie study Hebrew?

ANSWERS:

- בן וג’ולי לומדים עברית.

- בן וג’ולי לומדים עברית בירושלים.

- בן וג’ולי לומדים עברית אצל שני מורים פרטיים בירושלים.

- איפה בן וג’ולי לומדים עברית?

- אצל מי בן וג’ולי לומדים עברית?

7. HebrewPod101 is Here to Help You Put Your Hebrew in Order!

Hopefully you feel like we’ve made some order of all the words you had bouncing around in your head. Armed with a better understanding of Hebrew syntax, you can now confidently string your vocabulary into coherent sentences, and even questions.

As you’ve seen, there are some differences between Hebrew and English, but there are also many similarities in how words are ordered. To really hone your skills after reading this article, go out and look for real-world examples. Focus on the order of the words you read or listen to. Read a short Israeli article online or watch Israeli movies with subtitles, and notice how the writer or speaker orders his/her words. Try to take note of the structures you find difficult, and give these extra practice.

Don’t be hard on yourself if you mix up the word order here and there. Remember that mastery takes practice, and that the effort you put into your Hebrew studies will definitely pay off in the long run. HebrewPod101 is here to help you along the way, so as always, let us know if there’s anything you would like us to clear up or any issues you feel we didn’t cover here.

Shalom!